From Iron Age Necropolis to Virgil's Mythological Battleground

Area Archeologica Caracupa-Valvisciolo • Monte Carbolino

Sermoneta's origins reach deep into prehistory, creating layered narrative possibilities spanning 3,000 years. The Caracupa Necropolis, discovered in 1901-1903, revealed 80 tombs from 830-580 BC containing bronze swords, amber necklaces, and ceramic vessels—the possessions of a thriving Iron Age community. These ancient inhabitants built the polygonal fortifications of Monte Carbolino between the 7th-6th centuries BC, possibly the oldest such construction in central Italy. The Roman poet Virgil immortalized their city, ancient Sulmo, in the Aeneid as one of the Volscian settlements that fought against the Trojan hero Aeneas when he arrived in Latium to found Rome's lineage.

The very name "Sermoneta" carries mythological weight. After Roman conquest, the town was renamed "Sora Moneta" honoring the goddess Juno Moneta, divine protector of warnings and money. Her temple in Rome housed the mint itself, and her name became embedded in this strategic hilltop for millennia. First documented in 1116 as "Sermoneta degli Annibaldi," the medieval town emerged under the baronial Annibaldi family who constructed the original fortress in the early 1200s. The Annibaldi built two towers—the Maschio, originally 42 meters high and taller than its current truncated form, and the smaller Maschietto companion tower—along with the first defensive walls and the Church of San Pietro in Corte inside the fortress.

Financial catastrophe struck the Annibaldi in the late 1200s, forcing them to sell their entire complex to the ambitious Caetani family in 1297 for the staggering sum of 140,000 gold ducats. This transaction, orchestrated by Pope Bonifacio VIII Caetani for his nephew Pietro II Caetani, transferred Sermoneta, Bassiano, and San Donato to a dynasty that would dominate southern Lazio for seven centuries. Under Caetani control, Sermoneta flourished as the center of their political and economic power, controlling the vital Via Pedemontana connecting Rome to Naples—the only viable route when the Via Appia remained impassable due to malarial Pontine marshes.

The 14th century saw dramatic expansion. The Caetani constructed the massive 22-meter Sala dei Baroni as their center for political and economic affairs. By 1446, Onorato III Caetani built the Loggia dei Mercanti, which served simultaneously as town hall, commercial exchange, and popular assembly venue. In 1470, he commissioned the famous Camere Pinte (painted chambers) with mythological frescoes by an unknown artist, possibly from Pinturicchio's school. These luxuriously decorated guest rooms with their frescoes depicting virtues and mythological scenes represented the zenith of Caetani cultural ambition.

The Borgia Takeover: Excommunication, Confiscation, and Architectural Transformation

Castello Caetani

The year 1499 brought the most dramatic rupture in Sermoneta's history—a story of papal conspiracy, forced exile, and the rule of Renaissance Italy's most notorious family. Pope Alessandro VI Borgia, using manufactured disputes between Sermoneta vassals and neighboring Sezze as pretext, issued the papal bull "Sacri Apostolatus Ministerio" excommunicating the entire Caetani family and confiscating all their properties. The violence was swift and brutal. Nicola Caetani had already been poisoned in 1494, allegedly by Matteo di Pesaro on orders from Cesare Borgia. In 1496, Giacomo V Caetani was lured to Rome under false pretenses, imprisoned in Castel Sant'Angelo, and executed. In May 1500, Bernardino Maria Caetani was butchered by Cesare's order in Sermoneta itself. Surviving family members fled into exile.

Alessandro VI awarded the castle and territories to his illegitimate daughter, the golden-haired Lucrezia Borgia, as part of his ambitious plan to create a Borgia-dominated feudal capital in central Italy. For four years (1499-1503), the woman history remembers as scandalous proved herself a capable and enlightened governor. She lived in the beautifully frescoed castle rooms and in 1501 issued the Statuta populi Sermonetani—an illuminated manuscript of progressive municipal statutes focused on protecting the weak, ensuring public order, and establishing fair taxation. This document, still preserved today, demonstrates Lucrezia's transformation from political pawn to "donna di potere" (woman of power), preparing her for her later role as Duchess of Ferrara.

Her brother Cesare Borgia and their father's architect Antonio Sangallo il Vecchio completely transformed the castle from aristocratic residence to military fortress. They destroyed the top floor of the Maschio tower and razed the Church of San Pietro in Corte to the ground without respect for the Caetani burials within. They constructed the massive Cittadella (fortress within a fortress), the Torre Nuova bastion, second defensive walls, the walkway, deep fossato (moat), and equipped bastions with cannoniere (cannon ports). The current castle appearance largely reflects these Borgia modifications. Cesare's ceremonial sword—a magnificent cinquedèa engraved with Julius Caesar imagery and called "The Queen of Swords"—later entered the Caetani collection and remains exhibited in the castle today, a tangible link to the usurper's presence.

The Borgia interlude ended abruptly in August 1503 when Alessandro VI died. Pope Julius II immediately restored the Caetani to their holdings, and the family returned from exile to reclaim their ancestral seat. They transformed the military fortress into a social and educational center, inaugurating Sermoneta's golden age when it became a major economic, political, and cultural reference point for the entire region.

Lepanto's Hero and His Sacred Vow: The Madonna Appears in Battle

Rievocazione Storica della Battaglia di Lepanto

October 7, 1571 brought Sermoneta its most celebrated heroic moment. Duke Onorato IV Caetani, appointed Comandante Generale della Fanteria Pontificia (Commander General of Papal Infantry), led his forces aboard the galley "Grifone" at the Battle of Lepanto off the coast of Greece. This massive naval engagement pitted the Holy League against the Ottoman fleet in what would become the beginning of Ottoman naval decline. During the battle's fiercest and most desperate moment, with death seemingly imminent, Onorato's thoughts turned to a humble roadside shrine—a small Madonna image in a tabernacle at the beginning of the mulattiera (mule path) leading up to Sermoneta from the plain below.

The Christian fleet achieved complete victory, marking a turning point in Mediterranean power dynamics. Upon his triumphant return to Sermoneta, the entire town celebrated. His wife, Duchess Agnesina Colonna (a strategic marriage alliance with the rival Colonna family), waited at the castle gates. True to his vow, Onorato constructed the Chiesa della Madonna della Vittoria, where he would eventually be buried.

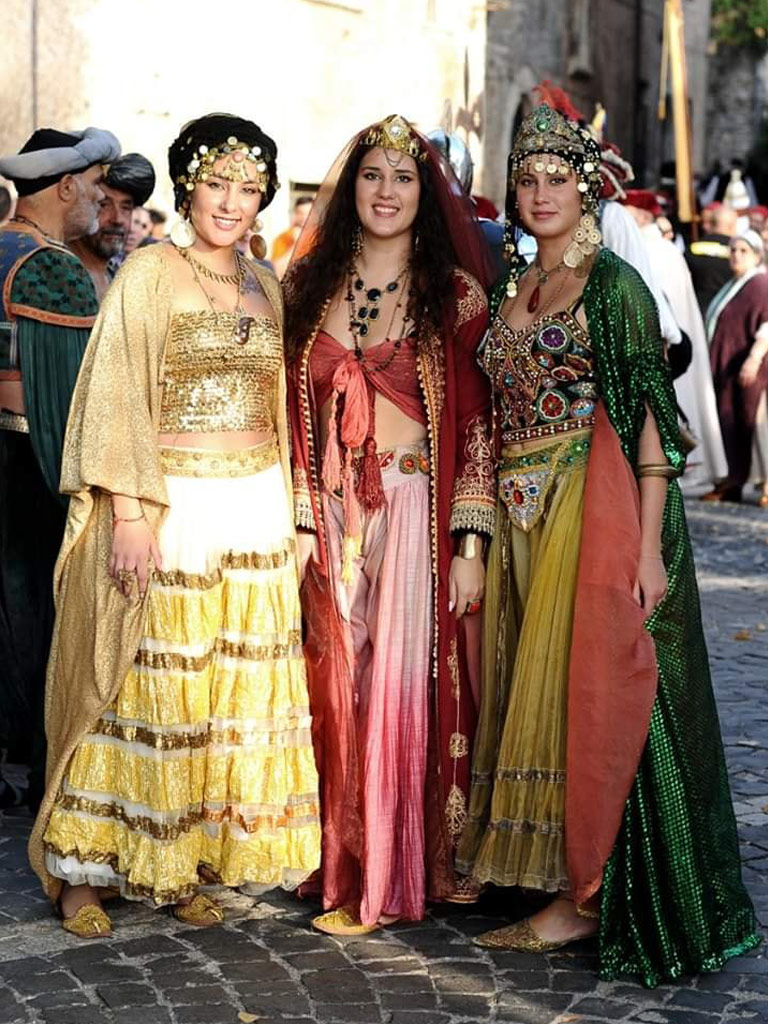

This story remains living tradition in Sermoneta. Every second Sunday of October since 1571, the town holds an elaborate rievocazione storica (historical reenactment) with over 130 participants in authentic Renaissance costumes from the 1571 period. The celebration begins three weeks earlier with neighborhood festivities in Sermoneta's five rioni (Borgo, Torrenuova, Valle, Castello, Portella), each decorated with colors and symbols. Knights compete in the Palio Madonna della Vittoria equestrian games for a prize banner. On the main day, the dramatic corteo storico (historical procession) recreates Onorato's victorious return—drums, trumpeters, and sbandieratori (flag throwers) in Caetani gold and vermillion lead the Duke into town, where Duchess Agnesina departs the castle with knights, ladies, pages, and nobility for their emotional reunion in the piazza before processing to the cathedral for thanksgiving to the Madonna.

Napoleon's Pillage and the Modern Foundation

The French Revolution's shockwaves reached Sermoneta on February 11, 1798, when General Louis Alexandre Berthier's army occupied Rome and proclaimed the Roman Republic. French forces confiscated all Caetani properties. When they stormed Sermoneta's castle, they systematically looted treasures and stripped 30 cannons from the fortifications. The family archives, fortunately transferred to their Roman palazzo in 1780, escaped destruction. Widespread rebellions against French occupation erupted throughout the Papal States in 1798-1799, with requisitions and forced contributions creating dramatic economic devastation in the Department of Circeo, which included Sermoneta.

After Napoleon's fall, the Caetani regained control, but the 19th century brought slow abandonment as the family's attention shifted primarily to Rome. The castle fell into disrepair, used for a time as a military warehouse. Only at century's end did the Caetani return their focus to restoration. Gelasio Caetani (1877-1934), a civil and mining engineer trained at Columbia University and WWI hero who engineered the famous Col di Lana mine explosion that destroyed Austrian positions, undertook massive restoration efforts while simultaneously publishing major works reorganizing family archives—"Domus Caietana" and "Caietanorum Genealogia."

Princess Lelia Caetani, last direct heir, founded the Fondazione Roffredo Caetani on July 14, 1972. When she died without heirs on January 11, 1977, the foundation inherited the castle, the Gardens of Ninfa, and other properties, ensuring their preservation and public access. Today, the Fondazione manages the castle with guided tours required for all visitors, hosts the prestigious Festival Pontino di Musica each summer (founded in 1963 by Lelia and her husband Hubert Howard), and maintains the Campus Internazionale di Musica bringing 100+ students worldwide for masterclasses.

Castello Caetani: Towers, Painted Chambers, and Prisoner Graffiti

Castello Caetani — Maschio, Sala dei Baroni, Piazza d'Armi

The Castello Caetani dominates Sermoneta's skyline from the highest point of the medieval borgo, commanding views across the entire Pontine Plain to the Tyrrhenian Sea and Monte Circeo promontory. The architectural complex represents extraordinary historical stratification—13th-century Annibaldi foundations, 14th-15th century Caetani expansions, 16th-century Borgia military fortifications, and modern restoration—creating one of Lazio's most articulated and best-preserved military architectures.

The Maschio (main tower) originally stood 42 meters tall, constructed with small squared stone blocks and pointed Gothic bifora windows decorated with marble columns on each floor. Built as a residenza fortificata (fortified residence) typical of early 13th-century Roman baronial families, it housed the lord's bedrooms and served as final refuge during enemy attacks. The structure was completely independent from the rest of the castle, connected only by two wooden drawbridges that could be raised. If the entire complex fell to enemies, personnel and servants would retreat inside the Maschio as last defense. Today it retains only three of its original four floors, truncated during Borgia modifications. The upper rooms preserve the studio and camera da letto (bedroom) of the last Caetani residents, including remarkably the original four-poster baldacchino bed of the castle lord.

The Maschietto, a smaller counter-tower attached to the Maschio's south side, completes the defensive core. These two towers dominate the vast Piazza d'Armi, a quadrangular courtyard with a central cistern that once held the Church of San Pietro in Corte (destroyed by the Borgias). The piazza functioned as military assembly area, market space, and community gathering point.

The Sala dei Baroni, constructed in the 14th century and modified by the Borgias in the 15th, stretches 22 meters long, divided into four bays by three pointed Gothic arches. This immense hall served for political assemblies, economic negotiations, and grand banquets—the beating heart of Caetani feudal administration. Visitors today can walk its length and imagine the duke's court gathered here for councils of state or elaborate feasts cooked in the enormous cucine (kitchens) where a single camino (fireplace) was large enough to roast an entire ox.

The Camere Pinte (painted chambers), commissioned by Onorato III Caetani in 1470, represent the castle's artistic pinnacle. Three rooms designated for important guests feature frescoes by an unknown artist, probably from Pinturicchio's school. Two rooms display mythological figures and allegorical scenes including the seven virtues. The frescoes' jewel-like colors—azure blues, vermillion reds, gold leaf details—transport viewers to Renaissance splendor. Original furnishings remain, including the four-poster bed and period furniture, offering rare tangible connection to 15th-century aristocratic life.

The Casa del Cardinale, a fortified building within the complex, houses the Sala del Cardinale featuring a Madonna con Bambino e i santi Pietro, Stefano e Giovannino painted in 1541 by Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta, the town's most famous Renaissance painter. Here also hangs the mysterious portrait of a young prince whose identity remains unknown—the sad-faced boy believed to be the child ghost whose cries echo through the dungeons.

One of the castle's most evocative spaces is a room displaying firme (signatures) of illustrious visitors scratched or carved into the walls—emperors Federico II and Carlo V (who visited April 2, 1536 with 1,000 knights and 4,000 infantry), popes Gregorio XIII (1576) and Sisto V, and other personalities. Among these graffiti appears a pentagramma (musical staff) carved by composer Roffredo Caetani, last Duke of Sermoneta, whose presence still haunts these stones.

The Borgia additions—the Cittadella with its three winding ramps and two drawbridges, the Rivellino defensive outwork, the massive muraglione supporting the walkway, the deep fossato, and cannoniere-equipped bastions—transformed the castle into a virtually impregnable fortress. The Grande Batteria, a long covered corridor, provides access to the camminamento di ronda (sentry walkway) circling the walls, offering panoramic views of the verdant countryside between Sermoneta and Norma, framed by the imposing Lepini mountains.

Churches Layered on Pagan Temples: Cistercian Gothic and Renaissance Treasures

Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta • Chiesa di San Michele Arcangelo

The Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta in Cielo, Sermoneta's main church, embodies architectural and spiritual layering spanning two millennia. Tradition and archaeological evidence indicate it rises on the foundations of an ancient temple dedicated to Cybele, the Phrygian mother goddess whose cult persisted into the late 5th century AD. The current structure originates in the 12th century when it was built in Romanesque forms with a basilica plan and three naves. In the 13th century, Cistercian master builders from the nearby Fossanova Abbey school transformed it into the Gothic structure visible today—acquiring greater spatial amplitude and vertical thrust through a new system of cross vaults requiring prismatic pilasters added to existing supports, a technique introduced at Valvisciolo Abbey in the 12th century.

The cathedral's 24-meter Romanesque campanile (bell tower), predating the Gothic renovations, dominates Piazza Santa Maria. Built on a square base, it rises through six levels divided by cornices, each level featuring elegant bifora windows with paired marble columns and rounded arches. Originally it had additional floors destroyed by lightning. The tower's exterior displays decorative ceramic basin inserts and brick patterns characteristic of 12th-13th century Lazio church architecture. A Gothic portico with two pointed arches and cross-vault ceiling supported by marble columns provides the cathedral entrance. The lunette above the portal contains a 15th-century fresco attributed to Pietro Coleberti da Piperno depicting the Virgin with Child and Saints—the first artistic awakening after centuries of decline.

Inside, the three naves all feature Gothic cross vaults terminating in a square apse (originally semicircular) flanked by lateral chapels. The interior preserves an austere Cistercian character in its structural elements while Renaissance and Baroque additions provide artistic richness. The Cappella degli Angeli (Chapel of Angels) houses the cathedral's greatest treasure: the Madonna degli Angeli, a tempera and gold leaf painting on wood panel created around 1452-1456 by the Florentine master Benozzo Gozzoli, student of Fra Angelico. The work was donated to Sermoneta by the Roman Senate in 1480. In this cuspidate altarpiece, the Virgin holds a model of Sermoneta itself—scholars recognize this as the oldest surviving visual representation of the town, with the cathedral, campanile, walls, Torre di San Lorenzo, Church of Sant'Angelo, and borgo houses clearly distinguishable. Gozzoli's luminous colors and graceful figures herald the Renaissance arriving in this mountain territory.

The choir behind the altar, financed by the brothers Flaminio and Alessandro Americi in memory of their father Pietro and completed 1600-1606, displays magnificent frescoes of Marian stories (Nativity of the Virgin, Assumption, Dormition, Presentation at the Temple, Marriage to Joseph, Annunciation, Visitation) painted by the workshop of Bernardino Cesari (1571-1622), brother of the more famous Cavalier d'Arpino. Duke Pietro Caetani later commissioned the wooden choir stalls carved with Caetani wave symbols. The monumental wooden baldacchino altar by Giuseppe Baccari (1683) and the facing wooden crucifix by Francesco Cavallini (1689) represent Baroque additions.

An unsettling 15th-century fresco of the Giudizio Universale (Last Judgment) covers the interior wall by the entrance, its dark and dramatic imagery creating an atmosphere of mystery and mortality. Another notable painting depicts the seven deadly sins in vivid, disturbing imagery. Throughout the cathedral, visitors find Templar and esoteric symbols. On one of the entrance steps, worn almost smooth by centuries of footsteps, appears a faint Triplice Cinta (Triple Enclosure) graffito. The doorway jambs display overlapping crosses pattées and a Centro Sacro symbol with eight rays. These mysterious markings connect the cathedral to the broader network of Templar sites throughout Sermoneta territory.

The Chiesa di San Michele Arcangelo, one of Sermoneta's oldest (early 11th century origins), underwent 13th-century Gothic transformation similar to the cathedral. Though now converted to an event space, its Romanesque three-nave interior with Gothic elements and cross vaults preserves anonymous frescoes and an 18th-century organ. The Gothic portico, unfortunately covered in modern white plaster, hints at its former elegance. Inside, a breathtaking Crocifissione fresco captures the Crucifixion's dramatic moment.

The Chiesa di San Giuseppe (1525), commissioned by the Caetani family, presents a white facade preceded by a short staircase. The single-nave interior features six lateral chapels. This church serves as focus for Sermoneta's patron saint festival every March 19, when the statue of San Giuseppe processes through town accompanied by the municipal band.

The Chiesa della Madonna della Vittoria, built by Onorato IV Caetani to fulfill his Lepanto vow, contains the Madonna effigy that appeared to him during battle. Onorato is buried within the church he promised to build in his moment of desperate faith. Each October, the Madonna statue processes through Sermoneta's streets during Lepanto commemoration celebrations.

Templar Mysteries: The Circular SATOR, Cracked Architrave, and Hidden Treasure

Abbazia di Valvisciolo

Sermoneta territory preserves more significant Templar traces than any other area in Lazio, creating an atmosphere of esoteric mystery that permeates the landscape. Eight kilometers from town, nestled in the valley between Sermoneta and Bassiano, the Abbazia di Valvisciolo stands as the epicenter of these mysteries. This Cistercian abbey, possibly founded in the 8th century though more likely post-1128, features pure Romanesque-Gothic architecture in local stone with a famous rose window marked by a Templar cross pattée. The Templars occupied Valvisciolo from the 13th to early 14th century, using it as a fortress and spiritual center.

Five concentric rings divided into five sectors like a target contain the five words of this magical square. Scholars debate its meaning: agricultural prayer, Christian cryptogram, or mystical formula. The circular formation may reference the Rotunda of the Anastasis (Church of the Holy Sepulchre) in Jerusalem, sacred to Templars and crusaders.

Local legend insists that when Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, was burned at the stake in Paris on March 18, 1314, the architraves of all Templar churches worldwide simultaneously cracked. Valvisciolo was among them. The crack remains visible today above the main portal entrance—physical evidence, believers claim, of mystical connection between Templar sites and their martyred leader's death hundreds of miles away.

The abbey's underground passages allegedly conceal the fabulous treasure of the Knights Templar, hidden at the end of 1308 when King Philip IV of France began arresting Templars. The treasure has never been found, though tunnels beneath Valvisciolo do exist, their full extent unknown. For 700+ years, local tradition has kept this treasure story alive, passed through generations as both history and hope.

Throughout Sermoneta's churches, Templar crosses and Triplice Cinta Druidica (Druidic Triple Enclosure) symbols appear mysteriously. These ancient Celtic markings—three concentric squares connected by crossing lines—decorate the floors and walls of San Michele Arcangelo, Santissima Annunziata, and the Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta. Templar tradition held that these symbols marked places of exceptional sacred and telluric (earth energy) power. Medieval travelers would have recognized these signs as indicating spiritually charged locations.

Convento di San Francesco

The Convento di San Francesco, dating to the 12th century, served as a known Templar stronghold. Though now semi-abandoned, its beautiful courtyard remains visible from outside, another node in Sermoneta's Templar network. These interconnected sites—abbey, churches, convento—create a sacred geography underlying the visible medieval town, inviting exploration of hidden knowledge and lost wisdom.

The Castello's Ghosts: Crying Child and Mischievous Jester

Castello Caetani — le stanze dei fantasmi

Two ghost legends pervade Castello Caetani and Sermoneta's streets, told by residents with matter-of-fact conviction as if describing living neighbors. These spirits aren't Hollywood monsters but melancholy presences evoking sympathy rather than terror.

The ghost of the child prince haunts the castle's underground dungeons and the Sala del Cardinale where his portrait hangs. This young boy of noble birth died violently in the dungeons under mysterious circumstances, possibly murdered for inheritance reasons or caught in succession intrigues. His identity has been lost to history despite his importance—he was significant enough to be painted but forgotten by time. Visitors and castle staff report hearing the child's lamenti (lamentations) and pianti (cries) echoing through castle rooms, particularly in the underground passages. Some claim to have seen his apparition—a small, sad figure in period clothing wandering the corridors. His heartbroken crying supposedly intensifies at certain times, as if reliving the moment of his death or seeking his lost family.

The portrait in the Sala del Cardinale depicts a serious young boy in Renaissance clothing, his eyes following viewers with haunting intensity. No inscription identifies him; no family claims him. This erasure of identity compounds the tragedy—he was killed and forgotten, doubly murdered.

The ghost of the jester presents a completely different character—playful rather than tragic, mischievous rather than sorrowful. This young giullare (jester) was executed by order of Pope Boniface VIII himself, with some versions claiming the jester was the Pope's own relative, making the execution particularly cruel. Now his restless spirit roams both the castle and the streets of Sermoneta that were dear to him in life. The jester's sonagli (bells) can still be heard tinkling sadly through empty castle corridors when no one is present.

Unlike the child ghost who remains confined to the castle, the jester's spirit roams freely through the borgo, continuing in death the wanderings he enjoyed in life. He makes mischief with merchants in their shops, plays jokes on tourists passing through the narrow vicoli, and is blamed for small mysterious occurrences—items moved, doors opened, sounds heard. Many Sermoneta residents can recount stories of his pranks with affectionate exasperation. His presence is playful but tinged with melancholy—the sadness of one unjustly killed who cannot fully let go of the world.

The jester's story embodies a recurring theme in Sermoneta's history: the ruthlessness of the powerful crushing the innocent. Boniface VIII, who brought the Caetani to power and whose ambitions shaped the town's fate, also destroyed those who displeased him, even family. The jester's eternal mischief might be revenge, or simply the inability of a playful spirit to accept the finality of death.

The Caetani Dynasty: Popes, Poisoners, Warriors, and Artists

The Caetani family dominates Sermoneta's history from 1297 through 1977—680 years of nearly unbroken control creating a through-line connecting disparate eras. From ruthless medieval pope to enlightened 20th-century artists, the dynasty's evolution mirrors broader Italian transformation from feudal power to cultural stewardship.

Pope Bonifacio VIII (Benedetto Caetani, c.1230-1303) stands as the family's towering, controversial patriarch. Born to Anagni nobility, trained as canon lawyer and diplomat, he became pope in 1294 after the abdication of Celestine V (whom Bonifacio allegedly influenced to resign, then imprisoned in Fumone fortress where he died, fueling centuries of murder rumors). Bonifacio proclaimed the first Jubilee/Holy Year in 1300, published the Liber Sextus codifying canon law, and advanced the strongest claims of any pope to temporal power, declaring papal authority over all monarchs. His supreme arrogance and ruthless accumulation of territory for the Caetani family made him enemies. Dante placed him in the Eighth Circle of Hell among the simoniacs; Franciscan poet Jacopone da Todi called him "novello anticristo" (new antichrist). His death came after humiliation at Anagni when French forces attacked him (the "Outrage of Anagni"). Yet his brilliance as politician and use of papal office to establish family power created the Caetani state that dominated southern Lazio for centuries.

Onorato III Caetani (died 1479) built Sermoneta's golden age as cultural and economic center. He commissioned the Loggia dei Mercanti (1446) and Camere Pinte (1470), hosted Emperor Frederick III with great splendor (1452), served as Protonotary and Logoteta of the Kingdom of Naples, and married into the rival Orsini family. But his reign included brutal moments. During a revolt at Ninfa, he personally chased rebels across castle terraces until they jumped to their deaths rather than surrender. One rebel was a subdeacon with church immunity, leading to Onorato's excommunication and public humiliation—he was forced to go seminude with a rope around his neck, holding a rod, to be beaten by the Archpriest of Ninfa after paying an enormous fine.

Nicola Caetani (c.1440-1494) and his brother Giacomo V (died 1500) represent the family's martyrs, victims of Borgia conspiracy. Nicola, an expert swordsman trained by legendary condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni, guarded the 1492 conclave that elected Alessandro VI Borgia—bitter irony, since Alessandro would orchestrate his destruction. Nicola was poisoned in 1494, allegedly by Cesare Borgia's agent. Giacomo was lured to Rome in 1496 under false pretenses, imprisoned in Castel Sant'Angelo, tried, and executed. Their nephew Bernardino Maria was butchered in Sermoneta in May 1500. These murders cleared the path for Borgia seizure of Caetani holdings—dramatic evidence that even papal guard service offered no protection against papal vengeance.

Lucrezia Borgia (1480-1519) governed Sermoneta 1499-1503, demonstrating capacity far beyond her notorious reputation. Illegitimate daughter of Pope Alessandro VI, blonde and blue-eyed, well-educated in humanities, she endured three political marriages orchestrated by her father. Scandal attached to her—accusations of incest with father and brother Cesare, rumors of poisoning—but serious historians recognize most as propaganda from Borgia enemies. During her Sermoneta rule, she issued the progressive Statuta populi Sermonetani (1501), an illuminated legal code emphasizing protection of the weak, fair taxation, and public order. Her transformation from "political pawn" to "woman of power" occurred in these years. After Alessandro's death, she became Duchess of Ferrara, demonstrating genuine charity, arts patronage, and devoted motherhood—a redemption arc from maligned youth to respected matriarch.

Cesare Borgia (1475-1507) embodies Machiavellian ruthlessness—the model for Il Principe. Cardinal at 18, he renounced the position to become military leader, taking the title Duke of Valentinois (Il Valentino). Brilliant strategist combining cunning, violence, and political calculation, he allegedly killed his brother Giovanni (found in the Tiber, 1497), ordered the strangulation of Lucrezia's husband Alfonso d'Aragona (1500), and orchestrated the poisonings and murders of multiple Caetani. At Sermoneta, he supervised military fortifications transforming residence to fortress. His ceremonial sword, the magnificent cinquedèa called "The Queen of Swords," remains in Caetani collection—a beautiful weapon associated with brutal acts. His rapid fall after Alessandro's death sent him to obscurity and death at 31 in Spain.

Onorato IV Caetani (1542-1592), Duke of Sermoneta, war hero of Lepanto, represents noble warrior archetype with genuine faith. His marriage to Agnesina Colonna united two feuding families. As Commander General of Papal Infantry at Lepanto (1571), his sacred vow to the Madonna during battle's darkest moment shaped the rest of his life. Keeping his promise by building Chiesa della Madonna della Vittoria demonstrated integrity and devotion. Pope Sixtus V created him Duke in 1586; Philip II of Spain awarded him the Order of the Golden Fleece.

The modern Caetani shifted from feudal lords to cultural preservationists. Gelasio Caetani (1877-1934), civil engineer and WWI hero, combined military valor (engineered the Col di Lana mine explosion) with historical scholarship, publishing three volumes of "Domus Caietana" and reorganizing family archives. His brother Leone Caetani (1869-1935), world-renowned orientalist, authored the 10-volume Annali dell'Islam and espoused socialist politics despite aristocratic background, eventually emigrating to Canada in disillusionment with fascist Italy. Roffredo Caetani (1871-1961), last Duke and accomplished composer, married American heiress Marguerite Chapin, who founded prestigious literary journals "Commerce" and "Botteghe Oscure" publishing major 20th-century writers.

Giardino di Ninfa — eredità di Lelia Caetani

Lelia Caetani (1913-1977), last heir, studied painting with Balthus and co-created with her mother and husband the extraordinary Gardens of Ninfa. Tall and ungainly but with striking "16th-century Italian" facial features, she embodied cultural fusion—English grandmother, American mother, Italian father. Her death without heirs ended the dynasty but preserved its legacy through the Fondazione Roffredo Caetani she established. The transformation from Boniface VIII's ruthless accumulation through Onorato IV's warrior nobility to Lelia's artistic preservation reveals how aristocratic families adapted across seven centuries, finally converting feudal inheritance into public cultural heritage.

Living Traditions: Polenta Rituals, Fire Festivals, and the Lepanto Reenactment

Piazza del Popolo • Campo Vecchio

Sermoneta's festival calendar creates opportunities rooted in authentic centuries-old traditions. Unlike invented tourist spectacles, these celebrations maintain genuine community participation and cultural continuity.

The Sagra della Polenta (mid-January, near Sant'Antonio Abate feast day) represents Sermoneta's most beloved tradition dating to the 1500s when Guglielmo Caetani imported corn seeds from America. This winter festival honors Sant'Antonio Abate, protector of domestic animals, historically when shepherds descended from Lepini mountains to have animals blessed. On Piazza del Popolo, polentari (polenta makers) arrive at 6 AM to light wood fires under traditional copper paioli (large pots). The preparation follows strict ritual: flour added "a pioggia" (like rain) just before boiling, whisked vigorously to prevent lumps. Some elderly women make the sign of the cross with wooden spoons before adding flour—medieval superstition to ensure success. After 40-50 minutes of constant stirring, when the crust detaches from pot edges and intense aroma signals completion, the polenta is blessed and distributed, served with salsiccia (sausage) in rich sugo (sauce). The Banda Musicale Fabrizio Caroso provides musical accompaniment, Sbandieratori Ducato Caetani perform flag-throwing exhibitions, and folk group Capo d'Asino plays traditional songs.

The Festa dei Fauni (March 18-19) blends pagan and Christian elements in the transition from winter to spring. Ancient Lepini mountain inhabitants lit great fires from pruned branches, asking the god Faunus for abundant harvests. The Catholic Church assimilated this pagan ritual, dedicating it to San Giuseppe, Sermoneta's patron saint. On March 18 at sunset (7:30 PM) at Parco Campo Vecchio near Porta San Sebastiano, Sermoneta's five rioni compete to build the tallest, most beautiful fauni—massive bonfires from olive tree pruning branches. The lighting ceremony creates spectacular flames illuminating the medieval walls. Fires burn all night while people cook meat, salsicce, and baccalà (cod) on the coals. March 19 brings the religious component: Santa Messa, solemn procession with San Giuseppe statue from cathedral to Chiesa di San Giuseppe and back, accompanied by the municipal band. Municipal offices close for this patron saint day, emphasizing its ongoing importance.

The Rievocazione Storica della Battaglia di Lepanto (second Sunday of October) ranks among Italy's finest historical reenactments, with preparation spanning three weeks. Sermoneta's five rioni (Borgo, Torrenuova, Valle, Castello, Portella) each hold neighborhood celebrations presenting knights for the Palio competition, decorating streets with banners in rione colors, hosting wine tastings, food, songs, and dances. The week before the main event features the Trofeo Madonna della Vittoria—equestrian games at the Campo Sportivo where knights compete for the palio (prize banner). Saturday brings conferences, Santa Messa, procession with the Madonna della Vittoria effigy, fireworks, and band concerts.

Sunday's main reenactment involves 130+ figuranti (actors) in meticulously accurate 1571 Renaissance costumes—doublets, hose, elaborate dresses, armor, weapons—all in Caetani heraldic colors of gold and vermillion. Throughout the day, actors portray Renaissance daily life, demonstrate period crafts, play historical games. The Sbandieratori Ducato Caetani execute spectacular flag-throwing routines. "Ars Historica" demonstrates historical fencing techniques. Archbusiers fire period weapons. Menestrelli (minstrels) provide music. The emotional climax comes with the Corteo Storico (historical procession): drums and trumpets announce Duke Onorato IV entering with soldiers, while Duchess Agnesina Colonna departs Castello Caetani with her entourage of knights, ladies-in-waiting, pages, and nobility. Their dramatic meeting in the piazza recreates the triumphant reunion after Onorato's return from Lepanto. Together they process to the cathedral for thanksgiving to the Madonna who granted victory, then return to the castle. The winning rione from equestrian competitions receives the palio banner. This elaborate production has occurred annually since 1571 (with modern intensification from the 1990s), making it one of Italy's oldest continuously performed commemorations.

The Secolare Fiera di San Michele (late September, September 26-29) revives the ancient agricultural fair when Lepini mountain livestock farmers gathered to buy and sell cattle at season's end. Recently recognized by Regione Lazio as a "manifestation of historic interest," the fair occupies 2+ hectares displaying agricultural products, animals, plants, artisan crafts, wine, olive oil, and street food. The "L'Olio delle Colline a Sermoneta" competition judges local extra virgin olive oils, followed by tastings of oil and local soups. Evening concerts feature major Italian artists. Butteri (cowboys) demonstrate equestrian skills.

The Sbandieratori Ducato Caetani, founded in 1996, merit special attention as cultural ambassadors. These 80+ members in gold and vermillion Caetani colors perform the ancient art of vaulting and hurling flags—elaborate choreographed routines recalling battles where Caetani dukes led troops. They've performed internationally (Melbourne, Sydney, Korea World Cup, Mexico, New York Columbus Day), bringing Sermoneta's traditions worldwide while maintaining local identity.

Culinary Traditions: Trombolotto Alchemy and Serpent-Shaped Victory Cookies

Sermoneta's culinary traditions offer authentic centuries-old recipes and unique local ingredients.

Trombolotto (Citrus Limon Cajetani) represents medieval alchemy translated to gastronomy. This wild lemon variety native to Sermoneta area has scientific name honoring the Caetani family. Its aromatic profile resembles cedar and bergamot. Cistercian monks, possibly Templars at Valvisciolo, developed the original condiment combining whole crushed lemons (juice, peel, essential oils) with extra virgin olive oil and 12-14 Mediterranean herbs gathered from Sermoneta's sottobosco (forest undergrowth)—aglio (garlic), prezzemolo (parsley), peperoncino (chili), melanzana (eggplant), funghi porcini, scalogno (shallot), pomodoro, sale, origano selvatico, nepetella (calamint), dragoncello (tarragon). The preparation uses a special mill crushing lemons and olives together, simultaneously extracting lemon essences and oil. After adding herbs, the mixture infuses for 30 days, developing complex flavor profile: sweet, salty, bitter, acidic, spicy, all balanced in green-gold liquid. In 1496, after Columbus returned with New World products, chili pepper was added, transforming the condiment completely.

The recipe nearly disappeared but was recovered by Fabio Stivali and Angela Concu of Gastronomia Storica Sermonetana after 35+ years of research into historical sources. They registered it as a trademark and produce it through their restaurants Il Giardino del Simposio and Simposio al Corso. Celebrity chef Heinz Beck created signature spaghetti recipes featuring it. Trombolotto's history—from medieval preservation necessity (masking rancid meat with amphoteric properties) through refined noble cuisine to near-extinction and modern revival—offers narrative of culinary knowledge preserved, lost, and reclaimed.

Polenta represents communal winter sustenance. Traditional preparation in copper paiolo over wood fire requires 40-50 minutes constant stirring, religious ritual of crossing with wooden spoon, and judgment of readiness by aroma and crust formation. Served on wooden board, topped with salsiccia, pork spuntature (ribs), abbacchio bollito, or rich sugo, it fed entire families racing to reach central meat piece—WWII-era memory of scarcity transformed to festival abundance.

Serpette (serpent-shaped cookies) commemorate the Battle of Lepanto victory. The serpent form references both the onda (wave) in Caetani family crest and the defeated Muslim enemy symbolized as serpent. Simple ingredients (sugar, eggs, flour) shaped like snakes create high-caloric winter specialty. Each cookie becomes edible celebration of Onorato IV's triumph, physical manifestation of legend.

Giglietti (lily-shaped cookies) reference the giglio (lily), heraldic symbol of Bourbon France, recalling Caetani-Bourbon alliances. Visciole (wild sour cherries, Prunus cerasus variety "Tosta Sermonetana") grow on Lepini mountains, harvested mid-July. Gastronomia Storica Sermonetana produces visciole sciroppate (in syrup), visciole all'Armagnac (with 30-year Armagnac), and aceto balsamico di visciole (balsamic vinegar). Used in crostate (tarts) for desserts but also with roasted game, fish, vegetables—sweet-tart flavor profile bridging categories.

Other local products include tartufo nero dei Monti Lepini (black truffle) hunted by multi-generation tartufai families; extra virgin olive oil from Itrana cultivar olives pressed in local frantoi; pecorino cheese aged in caves; lacchene con fagioli (wide pasta with beans allegedly appreciated by Pope Bonifacio VIII); various zuppe (vegetable and legume soups) from mountain peasant tradition. The Marchio SATOR collective label now identifies Sermoneta producers, creating shared branding for artisan quality.

Hilltop Vantage: Commanding the Plain from Olive-Crowned Stone

Belvedere • Via delle Scalette

Sermoneta's geography profoundly shapes its character and strategic importance. The town sits at 257 meters above sea level on the southwestern slopes of the Monti Lepini at the precise transition between mountain and plain. The approach is dramatic: visitors ascend a torturous, winding road climbing directly from the Pianura Pontina. The town appears suddenly—"d'un tratto bellissimo"—completely encircled by powerful walls, arroccato (perched) on its "colle d'ulivi" (hill of olive trees), clustered around the imposing castle.

The Monti Lepini form a distinctive limestone mountain range creating two dramatically different environments. Sermoneta's southwest-facing slope receives full sun throughout the day, creating ideal microclimate for olive cultivation. The color palette enchants: white limestone rocks, various greens of vegetation, earth tones of historical roofs and the plain, shades of blue for waters, rivers, canals, and the distant Tyrrhenian Sea. Extensive terrazzamenti (terraces) carved into hillsides centuries ago support olive groves, particularly the Itrana cultivar local specialty. The northeast-facing slope maintains more rugged mountain character with denser, more luxuriant forest vegetation descending to the Valle del Sacco.

Sermoneta functions as an "amazing balcony overlooking the Pontine Plain" with extraordinary panoramic views from multiple vantage points. The Castello Caetani's 42-meter Maschio tower offers the highest perspective, sweeping across the entire region. The Belvedere opposite Via delle Scalette provides vast panoramas. The Parco della Rimembranza, a small tree-lined square, looks over the Agro Pontino. The new Passeggiata Museale (about 1 km from Porta delle Noci to Porta Sorda) winds through centuries-old olive groves along the walls, offering views of both fortifications and landscape. From these heights, observers see: the Pianura Pontina stretching flat below, Monte Circeo promontory rising distinctively from the coast, the Tyrrhenian Sea and shoreline, on clear days the Isole Pontine (Pontine Islands) on the horizon, northward the Castelli Romani hills toward Rome, the nearby Garden of Ninfa in the valley, and the agricultural patchwork of reclaimed marshland from the famous 1930s bonifica (drainage).

This commanding position gave Sermoneta exceptional strategic value throughout history. As refuge far from the Saracen-ravaged coast and malarial Pontine marshes, it offered a "luogo sicuro" (safe place). Control of the Via Pedemontana connecting Rome to Naples (vital when Via Appia was impassable due to swamps) made it a "centro di controllo e passaggio" (center of control and passage) for southern Lazio. From castle and walls, defenders could observe the entire plain, seeing threats and opportunities approaching from any direction. This defensive advantage translated to political and economic power as Sermoneta taxed the only viable north-south route.

What makes Sermoneta unique among Italian borghi? Exceptional preservation first—described as "uno dei borghi medievali più affascinanti del Lazio" and "tra i meglio conservati del Centro Italia," earning Bandiera Arancione (Orange Flag) from Touring Club Italiano, designation as one of "I Borghi più Belli d'Italia," and inclusion in "100 Mete d'Italia." The medieval experience remains complete: original cinta muraria (city walls) with five gates, towers, and bastions; one of Lazio's best-preserved castles; medieval street plan forming "un dedalo di stretti (e a volte strettissimi) vicoli" (a maze of narrow, sometimes very narrow alleys); vertical organization with everything ascending toward the castle summit; construction throughout in local pale limestone.

The architectural mix of Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance elements coexisting creates distinctive character. Human-scaled medieval proportions—narrow passages, steep stairs, small piazzas—generate intimate atmosphere unlike modern urban spaces. The town seems to grow organically from its rocky hill rather than being imposed upon it. Multiple sources emphasize the "profondo silenzio" (profound silence) in inner streets, the sense of being "sospeso nel tempo" (suspended in time), stepping into "un'altra epoca" (another era). This atmospheric quality distinguishes Sermoneta from more touristy borghi that have lost authentic character.

The mystical and esoteric character pervades the town. More Templar traces survive here than anywhere else in Lazio—SATOR square inscriptions, Triplice Cinta Druidica symbols, Cistercian architectural elements, Valvisciolo Abbey's Templar cross and legends, hidden treasure stories. This creates atmosphere of mystery and concealed knowledge underneath the visible medieval structures. Few Italian towns are so completely associated with a single family. The Caetani shaped Sermoneta from 1297 through the 20th century, leaving the castle and all its iterations, city walls and urban plan, cultural institutions, economic development (introducing corn/polenta from America), Gardens of Ninfa. Today's Fondazione Roffredo Caetani continues their cultural mission, ensuring continuity.

The Medieval Jewish Community

Sinagoga Ebraica • Via Marconi (già Via degli Ebrei)

The medieval Jewish community adds another layer. From 1297 when Sabbatuccio giudeo swore fealty to Pietro Caetani through the 1569 papal expulsion decree, a flourishing Jewish community concentrated in Contrada degli Idoli (later Via degli Ebrei, now Via Marconi). The synagogue, constructed in 14th century in Italian architectural style with Romanesque bifora and pointed arch entrance, integrated into the town's fabric. Jews participated in civic life, sometimes in business partnerships with Christians, gaining autonomy from Rome's Jewish community. Early 16th-century property sales by Jewish families indicate beginning of exodus before the final 1569 expulsion. The synagogue and cemetery remained Jewish-owned until absorbed. "Sermoneta" became a surname for some Italian Jewish families, carrying the town's name into diaspora. This history of pluralistic community followed by forced exile adds dimension to the town's character—not just Catholic uniformity but centuries of cultural interaction erased by Counter-Reformation intolerance.

Atmospheric Essence: Stone, Silence, and Suspended Time

Museo della Ceramica • Museo Diocesano

For immersion, Sermoneta's sensory qualities create powerful atmosphere. Visually, the first impression of pale stone walls and castle emerging from olive groves as one ascends the winding road establishes dramatic entry. The stone palette—white/cream limestone buildings, gray stone paving, terracotta roofs, green vegetation—creates visual coherence. Light and shadow play dramatically in narrow alleys that suddenly open to vast panoramic views. Constant verticality—climbing, descending, looking up to castle or down to plain—generates spatial awareness different from flat urban exploration. Texture varies from rough limestone walls to smooth worn stone steps to iron balconies to wooden shutters. Human-proportioned medieval spaces create intimacy, sometimes claustrophobic passages opening to airy piazzas.

Auditorially, profound silence dominates inner streets. Footsteps echo on stone. Church bells mark time. Wind through olive trees provides natural soundtrack. During festivals, music, flag-snapping, crowds transform the soundscape completely. Tactilely, smooth stone worn by centuries of feet, cool air in shaded passages, rough limestone walls, steep stairs requiring careful footing all engage physical awareness. The atmospheric quality overwhelms: the "suspended in time" sensation of stepping into the past, mystery suggested by Templar symbols and ancient stones hinting at hidden knowledge, tranquility despite tourism maintaining sense of peace and escape from modernity, authenticity of a living place with genuine character rather than museum-piece, melancholy of beautiful abandonment in some areas creating presence of absence.

Geo-Locatable Points of Interest

Loggia dei Mercanti • Porta delle Noci • Giardino di Ninfa

The medieval street plan with clearly identifiable landmarks enables location-based exploration. Five gates punctuate the walls: Porta Romana (main entrance), Porta delle Noci (north extreme), Porta Sorda (south), Porta San Sebastiano (near Parco Campo Vecchio), and the vanished Porta del Pozzo (15th century, now only wall fragments remain). The Loggia dei Mercanti on Piazza del Comune, built 1446 by Onorato III Caetani, served as town hall, commercial exchange, and popular assembly venue. Its large round arches follow 15th-century quattrocento style while the side entrance maintains Gothic pointed arch. Today used for civil weddings and events, it appeared in the film "Non ci resta che piangere." The Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta on Piazza Santa Maria dominates the religious quarter. The Chiesa di San Michele Arcangelo near Porta delle Noci, one of the oldest (11th century origins), now serves as event space but preserves Romanesque three-nave structure with Gothic additions. The Chiesa di San Giuseppe (1525) on the main street, Chiesa della Madonna della Vittoria built by Onorato IV, and other smaller churches (Sant'Angelo, Santissima Annunziata, San Nicola) dot the borgo.

The Castello Caetani at the summit provides ultimate goal and primary exploration space. Its multiple named areas—Piazza d'Armi, Maschio, Maschietto, Sala dei Baroni, Camere Pinte, Casa del Cardinale, Grande Batteria, dungeons and prisons, kitchens and stables, walkways—each offer distinct spaces with historical associations. The Belvedere opposite Via delle Scalette serves as panoramic viewpoint. The Parco della Rimembranza provides another vista with monument. The Passeggiata Museale, approximately 1 km path through olive groves along walls from Porta delle Noci to Porta Sorda, offers exploration route with information displays and benches at panoramic points.

Beyond town limits, the Abbazia di Valvisciolo (8 km away, between Sermoneta and Bassiano) serves as Templar quest location with its circular SATOR, cracked architrave, underground passages, and treasure legend. The Convento di San Francesco near the cemetery, semi-abandoned with beautiful courtyard visible from outside, provides atmospheric secondary location. The Monumento Naturale del Monticchio features a limestone pinnacle and forest traversed by Fiume Cavata. The Garden of Ninfa, though not in Sermoneta proper, connects as Caetani-family-created paradise in ruined medieval city—potential reward location or side quest destination.

The street network itself—Via delle Scalette (pittoresque stairway street), Via Marconi (former Jewish quarter), Corso Garibaldi (main street), Piazza del Popolo—provides navigation structure. Vicoli (narrow alleys) create maze-like exploration encouraging discovery of hidden courtyards, unexpected viewpoints, artisan workshops, small shrines. The vertical organization means multiple levels—lower town near gates, middle residential quarters, upper aristocratic areas near castle—each with distinct character.

Synthesis: Multiple Threads for Exploration

Sermoneta's richness supports various approaches to understanding this remarkable place. For narrative exploration, the historical conflicts provide compelling storylines: the Borgia takeover with forced exile, murder, property confiscation, and Lucrezia's enlightened rule versus Cesare's brutality; the Battle of Lepanto with Onorato's battlefield vow and triumphant return; the French Revolution pillaging with Napoleon's soldiers stripping the castle; the Jewish community's rise and forced exodus; Templar mysteries and treasure hunts. Character archetypes span from ruthless Pope Bonifacio VIII through warrior-duke Onorato IV to artistic princess Lelia, offering diverse personality types and moral complexity.

For architectural and spatial appreciation, the perfectly preserved medieval environment with dramatic verticality, panoramic viewpoints, maze-like alleys, and specific landmarks enables rich exploration. The Templar symbols scattered throughout (SATOR squares, Triplice Cinta, crosses pattées) create layers of mystery. The castle's multiple named rooms and spaces provide varied exploration with historical context. The contrast between profound silence in deserted alleys and festival crowds in piazzas offers dynamic atmosphere.

For economic and social understanding, Sermoneta's history suggests trading dynamics (Via Pedemontana control, Loggia dei Mercanti commerce), agricultural systems (olive oil production, polenta cultivation, visciole harvesting), artisan crafts (ceramics, trombolotto condiment creation, traditional food preparation), and festival organization (Sagra della Polenta, Festa dei Fauni, Lepanto reenactment with costume preparation, neighborhood competition, procession choreography).

For supernatural and mystery enthusiasts, the two ghosts (crying child prince and mischievous jester) provide sympathetic spirits. The Templar treasure legend, underground passages of Valvisciolo Abbey, cryptic symbols requiring decoding, and the circular SATOR puzzle offer investigation opportunities. The castle's dungeons with prisoner graffiti, the mysterious child's portrait without identity, Cesare Borgia's sword as potential cursed artifact—all suggest supernatural or historical mystery threads.

The seasonal calendar structures year-round engagement: January's Sagra della Polenta circuit through multiple dates and locations, March's Festa dei Fauni fire lighting and San Giuseppe procession, May's Maggio Sermonetano spring events, late July's visciole harvest, July-August Festival Pontino di Musica, August's Sermoneta in Folklore international performances, late September's Fiera di San Michele agricultural fair, early October's Palio Madonna della Vittoria, second Sunday October's massive Lepanto reenactment. Each festival offers distinct visual spectacle, activities, and narrative context.

The film location history ("Non ci resta che piangere," "Il Racconto dei Racconti," "I Borgia") indicates visual appeal and "Hollywood del basso Lazio" nickname suggests meta-awareness of dramatic aesthetics. The Fondazione Roffredo Caetani's cultural programming (summer music festival, restoration workshops, international masterclasses, conferences) demonstrates ongoing creative activity rather than fossilized preservation.

The contrast between Sermoneta's medieval stone permanence and the drained Pontine Plain's 20th-century transformation creates temporal layering—ancient mountain settlement looking down on modern agricultural landscape, Via Pedemontana connecting to Via Appia, hilltop refuge versus coastal exposure. This juxtaposition of old and new, mountain and plain, stone and cultivated earth, silence and festival noise, provides rich thematic material for exploring memory, tradition, community, transformation, and the relationship between past and present.

Sermoneta offers not just setting but complete cultural ecosystem—geography shaping history, history creating legends, legends informing traditions, traditions maintaining community, community preserving place. This means source material that hangs together coherently rather than disconnected facts requiring artificial narrative glue. The town's story tells itself through visible remains, living practices, and continuous inhabitation across millennia. This authenticity creates immersive potential rare in historical settings, where visitors encounter genuine cultural depth rather than generic medieval tropes dressed in Italian costume.